Our post, “Internet Providers Want Control Over Your TV” sparked concern within the ranks of regional Comcast leadership, especially when this cross-posting of that article on MinnPost appeared. It caused them to take action to correct what they viewed as factual errors within the article.

While those (arguably) factual errors are corrected in the comments below the original post here and discussed within this article, Comcast’s “internet control” problem remains and I gained an unintended clarity about it from a conversation with a Comcast executive.

On Friday April 10th, I talked for an hour with David Diers, VP of Advanced Services for Comcast Twin Cities (he’s been involved in rollouts, for example, of Comcast’s Digital Voice, the 50/5 DOCSIS 3 service which I have at my office, and is now involved in accelerating the deployment of Comcast’s business services). Should mention that the setting up of this call was done by Tim Elliott (Disclosure: Tim is one of the Minnov8 team and involved with social media marketing for a firm engaged with Comcast and a friend of mine) so I went into this call with an open mind.

After letting the call sink in I realized that Mr. Diers regurgitation of the company positions and line were so well scrubbed (e.g., the comment here is mostly a cut-n-paste from Comcast press releases and FAQ’s) that the essence of the post in question was deflected and the overall issue remains: Comcast is attempting to control their internet pipe into your home or business and protect their cableTV franchise to your detriment, and arguably in a way that is already stifling innovation.

The internet is the most important development in human communication and connection since the telephone. It is already more profound in its impact than the development of the interstate highway system and is evolving. It is a fundmental infrastructure that will continue to accelerate (and increase efficiencies within) medicine, education, B2B/B2C commerce, while increasingly augmenting our human connections by allowing us to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of either geographical separation or time.

For anyone who reads Minnov8 knows, our position is that the ‘net is vital to 21st century competitiveness in the State of Minnesota. Optimal access is key to innovation, an imperative for collaboration, and increasingly a component in mission-critical business activities that cannot be ignored nor, quite frankly, controlled by any entity with a primary focus on their profits and stakeholders that ends up outweighing what’s in the public’s interests.

All that said, I do go back-n-forth over the need for broadband to be a public utility vs. providing a playing field (with rules that we call “regulations”) which allow for-profit internet providing companies to flourish and continue to do what Comcast has done: maximize their network and provide their customers with faster and better internet access.

THE CALL: OBJECTIVE MET & AN UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCE

Diers’ goal for our call was clearly to set the record straight. Mine was to hear him out and get more insight into their motivations and positions.

Diers’ goal for our call was clearly to set the record straight. Mine was to hear him out and get more insight into their motivations and positions.

While Mr. Diers achieved his goal, I ended up preparing for the call in advance by doing more analysis of the issue of control and Comcast’s stated positions and, ironically, emerged from this call stronger in my resolve that rules and regulations are a must if our State is not to be dependent upon any internet services provider working toward their own incentives vs. those that strategically ensure the public good is maintained and that innovation continues in an open, competitive and affordable internet.

The conversation David Diers and I had was amiable and pleasant, and started off by establishing one another’s credentials and why the call was happening. There were two key issues he wanted to clarify:

1) One key problem Comcast officials had with the post was my characterization of their executive escalation person’s response to my query over my ability to buy more bandwidth and have no caps. While her response to me was that “bandwidth caps are bandwidth caps” — and I’d have no recourse if I consumed more than Comcast’s 250GB cap — was incorrect since I can buy business services and have unlimited bandwidth. Their position is that the 250GB is remarkably generous since “just over 1% of our customers come even close to hitting those caps.”

In retrospect, I realize now that — even though I’m fairly certain I asked specifically about business services in a residential setting — I’ll give the executive escalation rep the benefit of the doubt and chalk this up to a miscommunication. Comcast does, in fact, offer unlimited bandwidth if one is to buy a business class service for their home and I’m guessing she thought I was asking about what was available for residential services only. I stand corrected.

2) The second problem they saw in my post was my characterization of Comcast simply cutting off services for those customers who overtly, or inadvertently, exceed the 250GB cap. Section IV of their Terms of Services (TOS) states, “Comcast prefers to inform customers of inappropriate activities and give them a reasonable period of time in which to take corrective action.” While that sounds reasonable, reading the entire TOS document shows that Comcast, “… reserves the right immediately to suspend or terminate your Service account and terminate the Subscriber Agreement if you violate the terms of this Policy or the Subscriber Agreement.”

Yes, it’s in their best interest to inform us but they’re not obligated to do so but I should’ve gone back to their site and re-read their TOS. Mea culpa and I stand corrected.

One reason I emerged more resolved after this call than before it was that these two corrections are ‘nits’ and the substantive issues brought up during the call were deflected with vanilla responses.

250GB Today…But What About Tomorrow?

The essence of my post was not just bandwidth consumption today, but rather what consumption will be in 2010 or 2011 and that my opinion is that their bandwidth cap is an anti-competitive move.

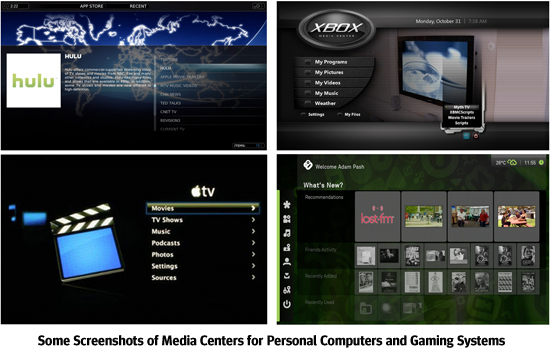

I tried to focus on the “control over tv” theme in the post and make the point that the rapid adoption of sites like YouTube and Hulu — and the increased use of media centers by everyday consumers of TV — is the threat they’re trying to stave off. I argue that these media center users will soon begin to demand even BETTER quality video to be delivered (e.g., rivaling what they get out of Comcast’s cableTV box) and that both the use of these media centers, and the bandwidth used to view this TV content NOT delivered via a Comcast cable box, are competitive and disruptive threats to Comcast’s cableTV franchise and the primary motivator behind the bandwidth cap.

Diers continually fell back on Comcast’s position and argued that only a tiny fraction of customers even came close to the 250GB bandwidth caps (and that they at Comcast are being incredibly generous with such a huge cap) and he never once took the media center piece head-on. So I gave him an example of my back-of-the-envelope calculation of consumption at my own household as my reasoning behind why Comcast’s positioning of the 250GB cap as “generous” is disingenuous at best:

+ A typical Standard Definition (SD) video stream is roughly 500kbps. One hour of video consumes about 221MB’s of bandwidth

+ But a typical High Definition (HD) video stream is roughly 1.2mbps. One hour of it would consume roughly 525MB (and that’s for highly compressed HD video)If we watched streaming SD video for 4 hours each day for 30 days, that would equal about 63GB’s of bandwidth used. But assume that we will demand a qualitative increase in our video to HD quality (which we already are after only two weeks of use), then that compressed one hour of HD video could easily meet or exceed 1GB an hour. If so, that 4 hours each day for 30 days of video consumption would equal roughly 120GB’s or approximately half of Comcast’s 250GB bandwidth cap for TV alone!). (Yes, I understand that one measurement is bits per second and the result is measured in bytes, but again this is back-of-the-envelope and it’s very close).

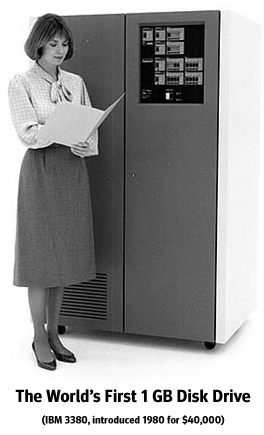

That’s just TV bandwidth consumption…if you now factor in the explosion in we “always-on, always-connected” people dealing with digital content by creating and uploading it, consuming it, storing and forwarding it and more, you have a 250GB Comcast bandwidth cap that will look as quaint as the world’s first gigabyte-capacity disk drive, the IBM 3380, which was the size of a refrigerator, weighed 550 pounds, and had a price tag of $40,000 when introduced in 1980…when we can buy a 500GB, 2lb, USB bus-powered drive at Costco for $79.

That’s just TV bandwidth consumption…if you now factor in the explosion in we “always-on, always-connected” people dealing with digital content by creating and uploading it, consuming it, storing and forwarding it and more, you have a 250GB Comcast bandwidth cap that will look as quaint as the world’s first gigabyte-capacity disk drive, the IBM 3380, which was the size of a refrigerator, weighed 550 pounds, and had a price tag of $40,000 when introduced in 1980…when we can buy a 500GB, 2lb, USB bus-powered drive at Costco for $79.

Why a Regulated Internet Provider Market Matters

The recent US financial markets meltdown has made many question “the free market” as well as the idealistic and naive belief in zero regulation, but like anything there are layers of complexity that need sorting out in order to protect economic incentives for profit, while ensuring that smart and strong business people don’t devolve into Snidley Whiplash-like characters once they’ve built their momentum, become a sole source provider, or are in a position to exhibit or capitalize upon monopolistic opportunities.

It’s my belief that Comcast is at a “Snidley Whiplash tipping point” since they hold a dominant market position in many areas they serve (including much of the Twin Cities), but during our call I focused on the Twin Cities and Minnesota and wanted to get a sense from Diers about Comcast’s position with respect to their dominance and its effects.

As a counter to my argument that they’re becoming a monopoly, Diers brought up their competition with Qwest and AT&T as examples of alternatives to Comcast’s broadband. While this is about as true as comparing a Ferrari to a Toyota Corrolla, I detailed my choices at home as evidence that competitive choices were no available to me: Comcast broadband at 16mbps download and 2mbps upload speeds or Qwest at what they describe as my “possible but we won’t know until we test” ability to get a connection that is 768kbps download and 384kbps upload speeds. While Qwest is about half the price of Comcast for internet service, anyone but the most casual internet user would even consider dropping down from Comcast’s speeds to such a low DSL speed from Qwest.

If a consumer only has one viable choice, isn’t that choice, by definition, a monopoly?

What I wanted to get to, however, were how bandwidth caps and controls had a negative effect on innovation and why I already believe that Comcast is stifling innovation by trying to control our TV’s and that their bandwidth cap is the first attempt at putting guardrails alongside their internet offering so they can better control what happens over their pipe and keep out the disruptors threatening their cableTV revenues.

I brought forth two examples of limiting choice and stifling innovation that I’d hoped Mr. Diers could relate to: the woefully inadequate nature of Comcast’s cableTV offerings as compared to the exciting innovations occurring with open source and commercial media center offerings, and their Digital Voice service more akin to an old line telephony provider than to a 21st century VoIP one:

1) COMCAST’S CABLE BOX: My TiVo interface from five years ago was delightful and packed with features. When DirecTV (my provider for 9 years) stopped supporting TiVo and delivered their own DVR, I was stunned with how antiquated its interface was compared with TiVo. But it wasn’t until I received my Comcast cableTV box a couple of months ago did I realize how laughingly bad an interface truly could be: it’s so much worse than DirecTV’s that I actually considered going back to DirecTV.

But NONE of them can compare to the incredible innovation with media center interfaces and the features packed into them. From easy and simple access to internet video from YouTube, Vimeo, CBS, Hulu, Revision3 and many others, it’s also trivial to access your iTunes music/tv/movie library, your iPhoto library if on a Mac, or point to media files residing on your file system. In short, the innovation in this category is nothing short of astounding and I’m constantly stunned at the enormity of accessible content at our fingertips through our Mac mini media center (and we’re discovering new stuff by the day!).

But it gets REALLY interesting when you realize that there is a robust and vibrant ecosystem of developers who are creating plugins for these media centers in order to connect them to an increasing number of video outlets. Why does this matter? If one wants a Fora.tv plugin…someone is working on it. Geeks wanted a Revision3 plugin to access their hidef shows…so someone built one and no one had to ask permission to make plugins.

There are no plugins for a Comcast cableTV box since it’s a closed and proprietary delivery mechanism solely controlled by Comcast and the only way to watch any internet-centric content on your television is through a media center or computer connected to it.

This is understandable since Comcast makes more than 50% of its gross revenue on its cable television business, these alternatives to what they offer are undoubtedly seen as a huge threat (and major consumer of bandwidth, thus one reason the cap is in place now before these media centers really take off). Like the record companies before them, one hopes they don’t make the same mistakes trying to control and manage the innovation surrounding them, but rather find ways to embrace, extend and support this innovation.

Diers immediately brought up that, “Did you know we’re playing in this same area, just like Hulu, with an offering called “FanCast”? Our objective is to figure out how to deliver video everywhere: the web, mobile device, etc.“

I responded with, “I do David….but this proves my point about why Comcast has to be net neutral and support all of the media center offerings. Don’t you find it curious that none of the developers of any of the upstart media centers out there have written a plugin for FanCast?“

2) COMCAST DIGITAL VOICE: It gets worse though. Comcast’s Digital Voice service, for example, is also as woefully inadequate as is their cable box software interface.

While Vonage offered a complete web-based dashboard to control all of its features — a service I first signed up for in early 2001 — my landline provider Qwest still doesn’t allow web-based management and Comcast’s Digital Voice is also lacking in features and has embarassingly inadequate capabilities in their web management offering. In this regard, Comcast is more like a plain old telephone company than they are a modern voice over internet protocol (VoIP) provider playing in a web world. Perhaps that is why they were traffic shaping early on rendering Vonage, a competing phone service, unusable.

I agree with many internet thought leaders that the internet ‘pipe’ needs to be dumb and the intelligence at the ends of it. The old joke is that if Ma Bell still had a monopoly on telephone service — making us all lease our Western Electric phones — we’d still be using rotary dial ones. Same thing here: Because Comcast doesn’t support media center offerings that could hang on the end of their internet connection, and instead controls the distribution via their own cable box, we end up with the crappy experience they provide since they have no competition for it.

We covered several other areas that could’ve been hour long calls alone:

- Their lack of monitoring tools so we can meter our bandwidth. It’s like Xcel Energy sending us a bill without a detailing of our energy consumption. Diers answer was what is in their FAQ’s on their website: they offer them now in their (PC only) antiviral suite, but for any consumer with multiple PC’s gaming systems and iPhones using the Wifi, a per-device monitoring solution is a joke

- Privacy is an issue. Since they are able to tell a customer what their consumption is at any given moment, how do we know trust that they’re not also able to view all our traffic? Know what URL’s we view? They say they’re only “aggregating traffic” by bandwidth, but how do we know? Diers had no answer.

I ended up winding down the conversation since it was clear that any meaningful discussion with Mr. Diers into competitive issues — beyond the press release or FAQ boilerplate stuff he espoused — was above his pay grade.

What do I think should occur next? As I stated at the outset of this post, this is a complex matter and finding the sweet-spot of open markets and regulation is a job best left to the professionals. But those people need to be very aware of why this is needed, examples of how it is (or could) stifle innovation and limit choice, and that the pipe needs to be as dumb as possible so we can add the intelligence to the ends where all the innovation occurs anyway.

So What Should You and I Do Now?

While the Obama Administration is working toward a National Broadband Policy, if you care about high speed broadband and how much control one (or a handful) of companies have over it, I’d urge you to make your voice heard by connecting NOW with the Minnesota Ultra High Speed Task Force members and let them know why and how this issue matters to you.

The Task Force needs to hear from you. They’ll be making their recommendations to the State Legislature this Fall and key portions of those recommendations are being formulated as you read this post. If they don’t hear from you and soon, they’ll never know an open, unfettered internet matters as much as we online participants do.

Minnesota Ultra High Speed Task Force Member Emails (full contact info here). UPDATE: Task Force chair, Rick King, asked that all email correspondence be directed to Diane Wells (email) as she’s compiling them and releasing a daily digest to the members.